Type Driven Development

Introduction

In our project workflow, we break down features to implement into tickets and developers pick them off one by one; Pretty standard & typical Agile/Kanban workflow. However while working on a feature recently, we came across on an interesting problem where our standard workflow didn't work out. Rather than trying to explain it in vague terms, I am going to start with a story.

TLDR

In case you don't want to dive in just yet, here is the idea we will cover in this post.

Think about the behaviour of your program in terms of data types & functions signatures. Next step is to

proveorderivea function that composes all of the types & signatures to implement the feature. Then carry on to implement each of the individual functions with the guarantee that all functions will compose together.

Now onto the story.

The Square Jigsaw Table

A Master Carpenter was asked to create a square table which was made of four big square blocks that connect together like a jigsaw puzzle. Four colours were to be used - Red, Green, Yellow & Teal.

The master carpenter had to go out of town and so he distributed the task among his four apprentices. He gave them following instructions to build:

- Each of you -

A,B,Cand,D, needs to build a square - One side should have semicircle slot approximately 10% radius

- The adjacent side should have a peg to fit the slot

- It should have one of four colours - Red, Green, Yellow or Teal

- If they don't perfectly fit at the end, I will finish the work once I am back

- Since each of you will be working on your own, keep everyone updated of your progress

During his journey, the craftsman was kept up to date by all of his apprentices. Their updates had the same gist.

I am progressing well with crafting the block. I had to make some slight modifications but it should be a quick fix once you are back.

On his return when apprentices presented master carpenter with the four blocks, he realized that they had a big problem. Turns out that while each of the apprentices followed his instructions, none had thought about how they would fit together and had made not-so-minor modifications.

Some of them even forgot that the goal of building these blocks was to combine them at the end!

Why did this happen?

I am sure that everyone has faced this problem at some point in their career. Feature/User Story gets broken down into small tickets and then developers pick up individual tickets to implement them. The expected result is that at the end they will all fit together. This happens because developers need to narrow their focus so that they can implement the ticket to the best of their ability. However the drawback is that the holistic view is lost and it is very easy to not realize how a minor change can impact the overall feature.

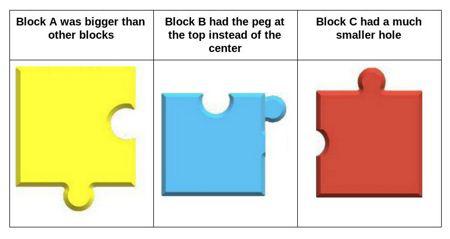

Specification & Proof

One way to avoid this issue is by defining behaviour of the final product with just enough information that everyone can work on their own with confidence. If we take the example of our four blocks, we can specify the behaviour of components using the block colours, pegs & holes of the four blocks and how they will connect. Here is what the apprentices were given to work with.

Now each of the apprentices can use the block's skeleton to create his/her own block as (s)he knows the size, colour and position of peg & hole.

Type Driven Development

We can achieve similar results with greater flexibility using domain model types & interfaces/function types. Before we look at "How?" let's first formally define it.

Type Driven Development lets you define the behaviour in terms of:

Components (Function Types)

Domain models (Data Types)

Once these specifications are in place, everyone can branch out and implement their individual tasks.

What does this mean?

In essence we want to "prove" our design and rest assured that after we have completed implementing the tickets, the components will work as expected and because the types compose. If you use statically typed programming languages this should be relatively straightforward to achieve.

Good news is that we don't need to use a formal specification tools like TLA+ or Coq but use plain old types and/or interfaces.

Let's use the example of online shopping with Type Driven Development to get a deep understanding of how it can be done.

Case Study: Online Shopping

Imagine that we have to build a service that:

- Takes a shopping list

- Checks for available items

- Orders available items

- Returns consolidated list of

- Ordered items

- Items not found and hence not ordered

This sounds straightforward and simple but defining all of this via program and ensuring it works well is never straightforward.

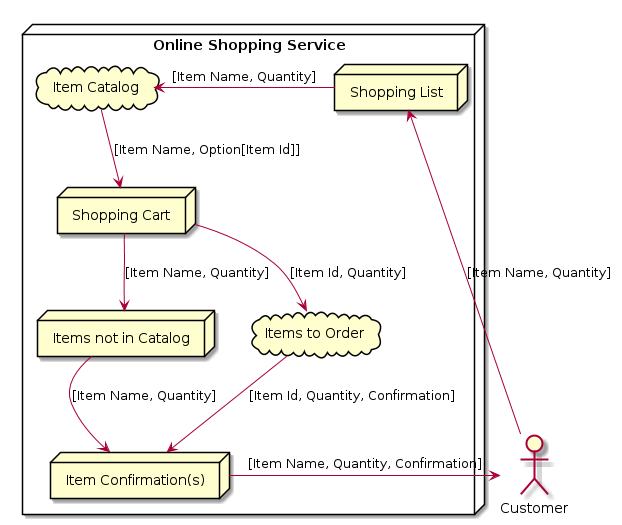

To start off with, here's a flow diagram that shows the above four steps along with some of the interim steps.

Note that we use cloud to represent external dependencies.

Code Demo

I will be using Scala's Cats library for the code demo as it allows us to use some of the concepts we need to compose our types.

Step 0: Structure

We start with four objects with predefined purpose as explained in the comments

package sandbox //Domain Models object DataTypes {} // Functions that will be used to transform data object Transformers {} // Functions that are used to represent outside services object Dependencies {} // We will use the above three objects and their inner components // here to prove that they will indeed work together object Specification {}

Step 1: Edge Behaviour: List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[ItemConfirmation]]

Based on the flow diagram, if we think from customer's perspective we know that:

- Customer has a

shopping listwhich consists of alistofitems&quantityto buy. - Upon ordering, customer will have a

listwhichconfirmsif theitems&quantityrequested were bought.

We can represent in code with following domain models & functions.

package sandbox import sandbox.DataTypes._ object DataTypes { // Primitive Data Types case class ItemName(name: String) case class Quantity(number: Int) case class Confirmed(ordered: Boolean) // Compound Data Types case class ShoppingListItem(item: ItemName, quantity: Quantity) case class ItemConfirmation( item: ItemName, quantity: Quantity, confirmed: Confirmed ) } object Specification { type Service[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[ItemConfirmation]] def proof[F[_]]: Service[F] = ??? }

Step 2: Dependencies

We also have two external dependencies

Catalog let's us translate ItemName into ItemId which is available within the system. Catalog behaves as follows:

- If

ItemNameexists in the system and hasItemId, it will return(ItemName, Some(ItemId)) - If

ItemNameexists but does not haveItemId, it will return(ItemName, None) - If

ItemNamedoes not exist in the system, it will not be returned by the system

This behaviour will be encapsulated by the function type QueryCatalog.

Shop is used to order items that can be found in the system. It behaves as follows:

- For given

ItemId&Quantity, it will return those details along withConfirmation -

Confirmationdenotes whether the quantity of item was successfully ordered or not

This behaviour is encapsulated by the function type OrderItems.

All this can be represented in the code as follows.

package sandbox import scala.annotation.StaticAnnotation import DataTypes._ object DataTypes { // ... case class ItemId(v: Int) // ... case class ShopOrderItem(id: ItemId, quantity: Quantity) case class CatalogItem(name: ItemName, id: Option[ItemId]) case class ShopConfirmation( id: ItemId, quantity: Quantity, confirmed: Confirmed ) } case class Note(message: String) extends StaticAnnotation object Dependencies { @Note("List[CatalogInfo] <= List[ShoppingListItem]") type QueryCatalog[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[CatalogItem]] type OrderItems[F[_]] = List[ShopOrderItem] => F[List[ShopConfirmation]] }

Step 3: Deriving Proof

We have defined the behaviour of our dependencies and also define how the overall system should behave from Customer's perspective.

Concepts: Monad, Functor & Higher Kinded Types

-

F[_] is Higher Kinded Type. That is, it is any type which has a "hole" which can contain another type. Common examples are

Option[Int],List[String]etc. -

Monad for our purpose is a Higher Kinded Type that has

flatMapimplemented for use. -

Functor is another Higher Kinded Type that has

mapimplemented.

We are defining our external dependencies via F[_] because they are IO operations over the network. Furthermore, we will to qualify F[_] as a Monad because we need to wait upon the IO operation to be completed and then work with the computed value, this is done by way of flatMap.

Let's see if we can now compose our dependencies to return List[ItemConfirmation]

package sandbox import cats.Monad import cats.implicits._ import sandbox.DataTypes._ import sandbox.Dependencies._ object Specification { type Service[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[ItemConfirmation]] def proof[F[_]: Monad]( queryCatalog: QueryCatalog[F], orderItems: OrderItems[F] ): Service[F] = (items: List[ShoppingListItem]) => for { catalog <- queryCatalog(items) orderedItems <- orderItems(catalog) } yield orderedItems }

If we try to compile the code, we get following error.

[error] found : List[sandbox.DataTypes.CatalogItem] [error] required: List[sandbox.DataTypes.ShopOrderItem] [error] orderedItems <- orderItems(catalog) [error] ^

The compiler is telling us that we need to define function/behaviour with following signature List[CatalogItem] => List[ShopOrderItem].

Let us define such a function type, use it within our proof as toShopOrder, transform catalog to shopItems and then recompile our code.

package sandbox // ... import sandbox.Transformers._ object Transformers { val toShopOrder: List[CatalogItem] => List[ShopOrderItem] = ??? } object Specification { type Service[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[ItemConfirmation]] def proof[F[_]: Monad]( queryCatalog: QueryCatalog[F], orderItems: OrderItems[F] ): Service[F] = (items: List[ShoppingListItem]) => for { catalog <- queryCatalog(items) shopItems = toShopOrder(catalog) orderedItems <- orderItems(shopItems) } yield orderedItems }

If we try to compile above code we get

[error] found : List[sandbox.DataTypes.ShopConfirmation] [error] required: List[sandbox.DataTypes.ItemConfirmation] [error] } yield orderedItems [error] ^

ItemConfirmation transformers

Now we know two things:

- We need to define the transformation function

shopToItemConfirmation: ShopConfirmation => ItemConfirmation - We need another transformation function,

itemToItemConfirmation: ShoppingListItem => ItemConfirmation. This is needed because we can have items not available in catalog.

Minor update: We need to redefine the behaviour/flow toShopOrder as (List[ShoppingListItem], List[CatalogItem]) => List[ShopOrderItem] because CatalogItem does not have all the information to be converted to ShopOrderItem so we will also need ShoppingListItem for complete conversion.

package sandbox // ... import sandbox.Transformers._ object Transformers { val toShopOrder: (List[ShoppingListItem], List[CatalogItem]) => List[ShopOrderItem] = ??? val shopToItemConfirmation: ShopConfirmation => ItemConfirmation = ??? val itemToItemConfirmation: ShoppingListItem => ItemConfirmation = ??? } object Specification { def proof[F[_]: Monad](...): Service[F] = (items: List[ShoppingListItem]) => for { // ... shopItems = toShopOrder(items, catalog) // ... } yield orderedItems.map(shopToItemConfirmation) }

Transformers to return complete List[ItemConfirmation]

In order to complete our proof, we need to figure out how to combine the following four domain models using existing Transformers and creating new ones if needed.

case class ShoppingListItem(item: ItemName, quantity: Quantity) case class CatalogItem(name: ItemName, id: Option[ItemId]) case class ShopConfirmation( id: ItemId, quantity: Quantity, confirmed: Confirmed ) case class ItemConfirmation( item: ItemName, quantity: Quantity, confirmed: Confirmed )

Based on these four domain models, following is one such solution which defines two function types:

case class Pairs(items: ShoppingListItem, confirmations: Option[ShopConfirmation]) val toItemConfirmation: List[Pairs] => List[ItemConfirmation] val getPairs: (List[CatalogItem], List[ShoppingListItem], List[ShopConfirmation]) => List[Pairs]

toItemConfirmation transformer

Let's conclude the spec by implementing the logic for toItemConfirmation.

package sandbox // ... import sandbox.DataTypes._ import sandbox.Dependencies._ import sandbox.Transformers._ object DataTypes { // ... case class Pair( listItems: ShoppingListItem, confirmations: Option[ShopConfirmation] ) } object Transformers { // ... val getPairs: ( List[CatalogItem], List[ShoppingListItem], List[ShopConfirmation] ) => List[Pair] = ??? val toItemConfirmation: List[Pair] => List[ItemConfirmation] = _.map { case Pair(item, None) => itemToItemConfirmation(item) case Pair(item, Some(confirmation)) => shopToItemConfirmation(item.name, confirmation) } } object Specification { type Service[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[ItemConfirmation]] def proof[F[_]: Monad: Functor]( queryCatalog: QueryCatalog[F], orderItems: OrderItems[F] ): Service[F] = (items: List[ShoppingListItem]) => for { catalog <- queryCatalog(items) shopItems = toShopOrder(items, catalog) orderedItems <- orderItems(shopItems) pairs = getPairs(catalog, items, orderedItems) } yield toItemConfirmation(pairs) }

Conclusion

Now if we look at complete specification, we can tell that following functions/types need to be defined.

val toShopOrder: (List[ShoppingListItem], List[CatalogItem]) => List[ShopOrderItem] = ??? val shopToItemConfirmation: (ItemName, ShopConfirmation) => ItemConfirmation = ??? val itemToItemConfirmation: ShoppingListItem => ItemConfirmation = ??? val getPairs: (List[CatalogItem], List[ShoppingListItem], List[ShopConfirmation]) => List[Pair] = ???

I found this style of defining types & "proving" the design to be quite beneficial for clarity of thought. And as I kept introducing types it was easier to see how the code would flow and whenever I felt something was unclear, I could start adding more details and thus get rid of nasty surprises at the earliest.

While experimenting with this style, I came across the concept of Dependent Types. It would be interesting to see where the two concepts intersect and where they are geometrically opposed.

Complete Source Code

For the sake of completeness, I will also provide the complete code of everything I have described in this blog post in one single section.

package sandbox import scala.annotation.StaticAnnotation import cats.Monad import cats.implicits._ import sandbox.DataTypes._ import sandbox.Dependencies._ import sandbox.Transformers._ import cats.Functor object Transformers { val toShopOrder : (List[ShoppingListItem], List[CatalogItem]) => List[ShopOrderItem] = ??? val shopToItemConfirmation: (ItemName, ShopConfirmation) => ItemConfirmation = ??? val itemToItemConfirmation: ShoppingListItem => ItemConfirmation = ??? val getPairs: ( List[CatalogItem], List[ShoppingListItem], List[ShopConfirmation] ) => List[Pair] = ??? val toItemConfirmation: List[Pair] => List[ItemConfirmation] = _.map { case Pair(item, None) => itemToItemConfirmation(item) case Pair(item, Some(confirmation)) => shopToItemConfirmation(item.name, confirmation) } } object Specification { type Service[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[ItemConfirmation]] def proof[F[_]: Monad: Functor]( queryCatalog: QueryCatalog[F], orderItems: OrderItems[F] ): Service[F] = (items: List[ShoppingListItem]) => for { catalog <- queryCatalog(items) shopItems = toShopOrder(items, catalog) orderedItems <- orderItems(shopItems) pairs = getPairs(catalog, items, orderedItems) } yield toItemConfirmation(pairs) } case class Note(message: String) extends StaticAnnotation object DataTypes { // Primitive Data Types case class ItemName(name: String) case class Quantity(number: Int) case class Confirmed(ordered: Boolean) case class ItemId(id: Int) // Compound Data Types case class ShoppingListItem(name: ItemName, quantity: Quantity) case class ItemConfirmation( item: ItemName, quantity: Quantity, confirmed: Confirmed ) case class ShopOrderItem(id: ItemId, quantity: Quantity) case class CatalogItem(name: ItemName, id: Option[ItemId]) case class ShopConfirmation( id: ItemId, quantity: Quantity, confirmed: Confirmed ) case class Pair( listItems: ShoppingListItem, confirmations: Option[ShopConfirmation] ) } object Dependencies { @Note("List[CatalogInfo] >= List[ShoppingListItem]") type QueryCatalog[F[_]] = List[ShoppingListItem] => F[List[CatalogItem]] type OrderItems[F[_]] = List[ShopOrderItem] => F[List[ShopConfirmation]] }